the fayoum

My dear friend,

The Fayoum Oasis, despite its name, is not actually an oasis. Instead, this lush region sixty miles southwest of Cairo is fed by a tributary of the Nile called Baher Yussef (Joseph’s canal, named after the biblical patriarch), a natural waterway that has been artificially widened and deepened at various points over the millennia. The canal helps regulate the flooding of the Nile, permitting overflow water to spill into a lake that the ancients called Moeris and present-day Egyptians call Qarun.

Water and wildlife drew humans here around 7200 B.C. Today, more than 9000 years later, the Fayoum still appeals to Cairenes and other travelers for its greenery and its relative serenity.

The first time we visited, we were escorted into and out of the region by the police. Don’t worry! This is normal. The local law enforcement officials don’t want any trouble with reckless or foolish tourists (since they’re the ones who will be held responsible if something goes wrong), and they figure that the best way to ensure our safety is to follow our car the entire time we’re in their district.

“You are from where?” our driver asked us on that first trip, while we were waiting at a checkpoint for the police to get themselves organized. We told him that our friends were from Great Britain and we were from the United States. He nodded, and then instructed us to say that we were all from the U.K. “England okay,” he explained. “America, more trouble.”

Apparently the police are more concerned about losing Americans, which means they’re more likely to follow us or even to forbid us from passing through. I’m not sure if this is because Americans are more foolhardy travelers, or because our embassy will make more of a fuss if we vanish. But it didn’t matter, in any case, because the police followed us anyway.

Delighted to be undercover, C. and I spent much of the rest of our journey practicing our Britishisms. “Scone!” I announced whenever an officer drew near. “Liverpool!” said C. Our friends shook their heads and patiently endured us.

Our intended destination on that first trip was the Valley of the Whales, Wadi el-Hitan, which I’ve mentioned to you before. Forty million years ago, when this desert was part of the Tethys Sea, whales swam here. They died and sank to the ocean floor, and their fossilized skeletons still rest in the dunes today.

The Jeep that we took to and from the Valley of the Whales spent less time on the paved highway and more time cruising up and over the sand dunes.

Of course there was the requisite sandboarding stop.

There was also, if you can believe it, a waterfall. Because the great Qarun is a saltwater lake, its levels need to be controlled so that the water doesn’t spill into farmland and turn the fertile soil brackish. To this end, two new lakes have been created nearby to handle more drainage. Since the northern lake is higher than the southern, the connection between the two is a waterfall that is quite small, and shrinking, but still a popular destination because it’s the only waterfall in Egypt.

(Despite their name, the so-called cataracts on the Nile are actually small rapids.)

We’d heard that the waterfall was underwhelming not only for its size, but also because the crowds were so thick at the lookout point and on the beach that it was hard to enjoy the site. We happened to visit on a day, however, when there had been rumors of planned protests in Cairo. Even though we were sixty miles away from the city, our driver told us, most people chose to spend the day at home in order to avoid any trouble. We saw about as many dogs and camels as we did humans.

It was a good reminder that the Fayoum is not as far from Cairo as it feels to me.

A trip to the desert surrounding the Fayoum Oasis is not complete without a glimpse of Magic Lake, so-named for the way its color changes with the passage of the sun across the sky. Depending on your guide and depending on the day, you might be offered a meal (fresh salad, grilled fish, stuffed cabbage rolls, steaming rice) cooked over a fire on its shores.

Birds wheel overhead while locals walk horses over the dunes and kids approach with necklaces of colored seashells that they’re hoping you will buy.

In my opinion, it’s better to spend your Egyptian pounds on Fayoum pottery, the craft that the region is best known for.

The bowl and mug that I brought back to Minneapolis last year bring me such joy! This year, we chose a very large plate that that might be a little harder to get home.

Tunis Village is the town in the Fayoum famous for these colorful, painted pieces. Strolling along the main road through the village, the visitor encounters beautiful shop after beautiful shop, each filled with bowls and plates and glasses and vases that are all similar in style and tone, but stamped with the signature of the individual potter.

It was a Swiss potter, Evelyn Porret, who brought the craft to Tunis when she moved here in 1977. In 1984, she established a ceramics school that trained locals in the art and helped them establish a new living.

The shops themselves are often decorated with ceramics, and the walls of the village are vivid with street art.

We’ve stayed twice now in Tunis Village in an airbnb with a garden, a shared bathroom, and a rooftop lounge. Breakfast (included!) consists of ful (mashed fava beans), eggs, and a tomato-yogurt salad.

The owners, an Egyptian and a German, moved to Tunis to escape Cairo during the pandemic. They rented a place with extra rooms, posted pictures on airbnb, and have been so successful that they’re currently constructing a new, bigger building a stone’s throw from this one.

It’s not hard to see why Tunis Village is so popular.

It’s only a two-hour drive from Cairo, but compared to that city, Tunis is serenity itself.

If one grows tired of walking the streets, there is plenty to do in and around town. C. and I took a tuktuk to a small Ptolemaic temple called Qasr Qarun, a labyrinth of rooms and corridors dedicated to the crocodile god Sobek. (In ancient times, much of this area was known as Crocodilopolis.) The temple is positioned in such a way that, during the winter solstice, the sun shines right through the entryway and rests on the altar.

In town, there’s a caricature museum that boasts not only many framed cartoons, but also a family of friendly cats.

Many of the images didn’t include captions, and when they did, the words were in Arabic. So we entertained ourselves by trying to come up with captions for our favorite pieces.

We also, once, went horseback riding on the beach. Although neither of us are experienced riders, our guide encouraged the horses to gallop and shouted to us, over the wind and the water, that it was better if we didn’t hang onto the pommel at all. I shouted back that I needed to hold onto something. The ride was beautiful and the setting was romantic, but I spent most of the ride thinking about how grateful I was for the travel insurance that would help cover the costs of my inevitable fall.

Whenever I’m in the Fayoum, I find myself already missing it—perhaps I’m always thinking ahead to the noise and smog of Cairo—and furtively planning another trip back.

The light is lovely in the afternoon; the goats canter on the dusty road in front of the mosque. The pottery gleams through the doorways of shops, and egrets rustle through the reeds along the lakeshore. It’s the kind of place that tends to inspire nostalgia even as one is dwelling in it.

That said, perhaps I can’t attribute this feeling to Tunis specifically. I feel often—and more often, these days, as the hour of our departure grows near—that I’m nostalgic for Egypt even as I’m walking its streets. Once or twice I’ve looked up from my laptop in our apartment and said to myself: “Remember that time we lived in Egypt?” as if we were already gone.

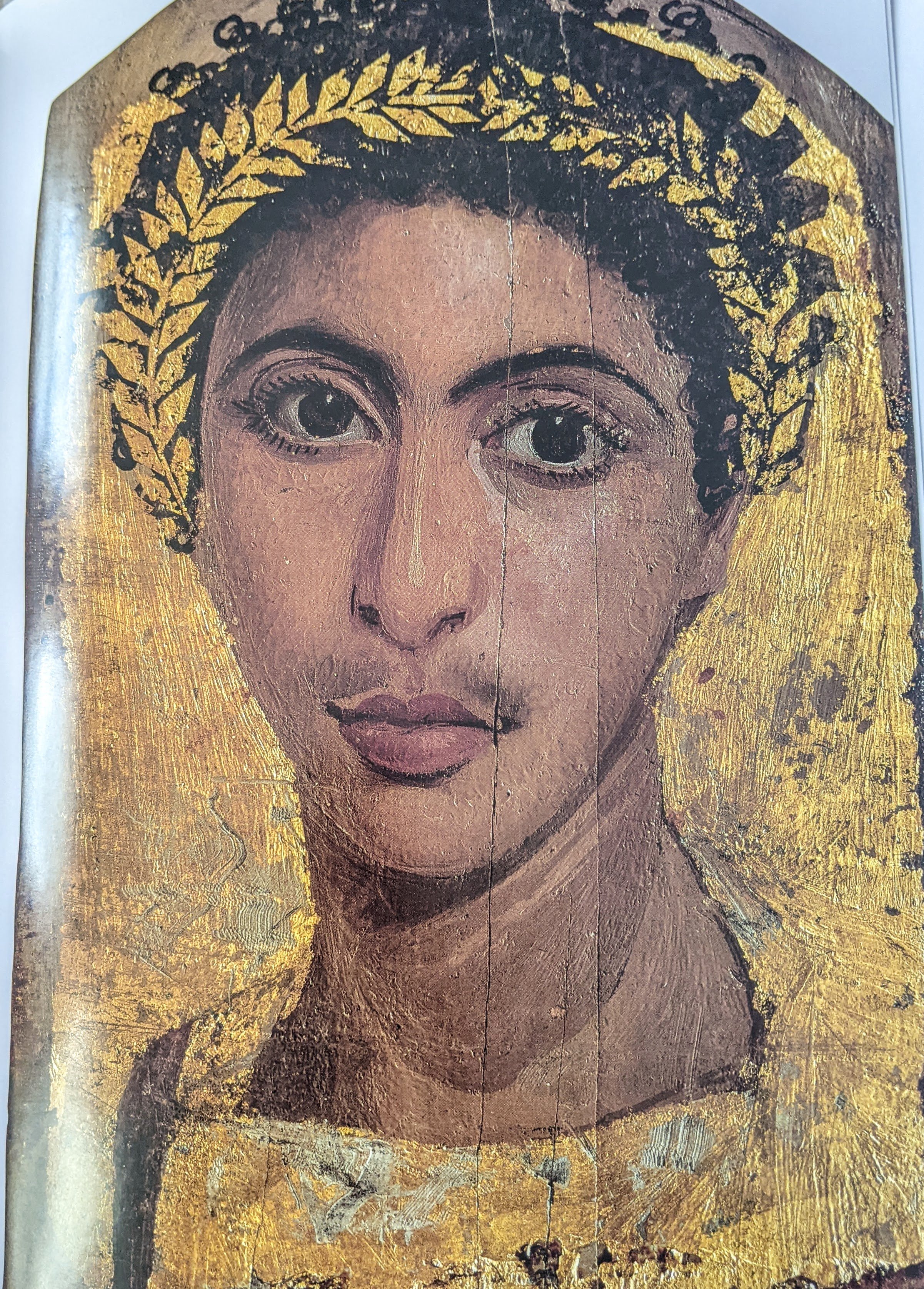

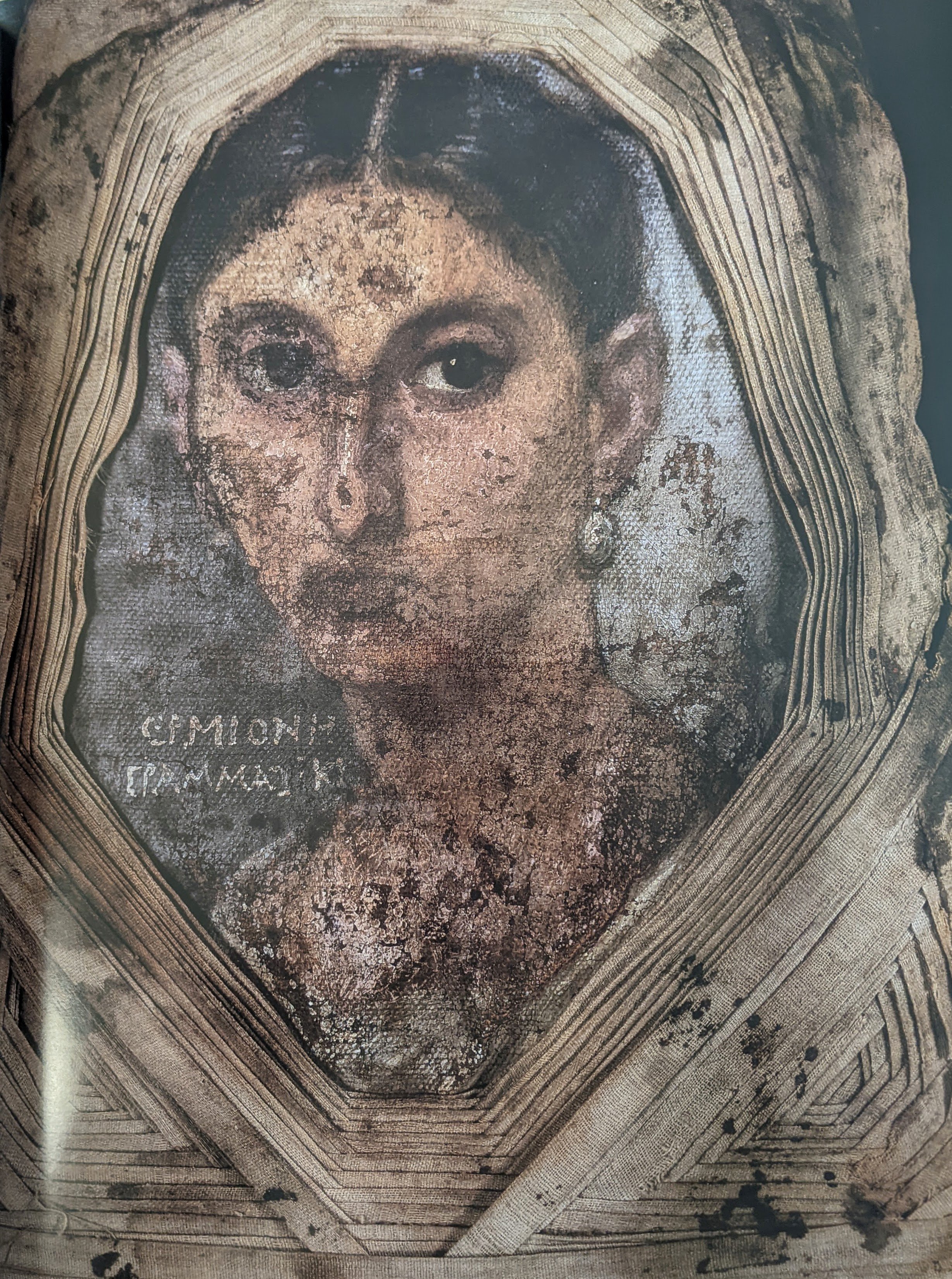

Internationally, the Fayoum is probably best known for the Fayoum Portraits: Roman-style paintings completed on panels and attached to mummies. Although ancient Egyptian sarcophogi also bore the faces of the deceased (otherwise, after death, the soul might not recognize the body to which it belonged), the images were idealized rather than realistic. The Fayoum Portraits, on the other hand, have been described as eerily lifelike, mysterious, and naturalistic in a way that shows the influence of Greek and Roman art in a region that was controlled by these empires between the 1st century B.C. and the 4th century A.D.

We don’t know whether the portraits were painted during life or after death. But we do know that they were painted on panels and inserted into the mummy’s wrappings. And perhaps part of the portraits’ mystique lies in how they were displayed: propped up inside families’ houses rather than buried in desert tombs. According to the ancient Greek Diodorus: “many Egyptians keep the bodies of their ancestors in costly chambers and gaze face to face upon those who died many generations before their own birth, so that, as they look upon the stature and proportions and the features of the countenance of each, they experience a strange enjoyment, as though they had lived with those on whom they gaze.”

In the gorgeous book The Mysterious Fayum Portraits, Euphrosyne Doxiadis evokes a sense of their history, allure, and beauty. Most of the paintings have been carried out of the country; few are left inside Egypt.

While I would prefer not to keep a mummy in my own house, no matter how dear the person was to me in life, I can understand the impulse to remain as close as possible to those who are absent and the effort to recapture, in some shape or form, that which has vanished. If my pre-nostalgia is any indication, we are always already living with what we have lost.

Back in Cairo now, I sip from a Fayoum mug every morning. My love for this mug is tinged with just a little sadness because every time I use it I think about how unhappy I’ll be on the day that it eventually breaks.

When I shared this sentiment with a good friend of mine, she told me about a Buddhist philosophy of time in which the past and future mingle in the present moment so that joys of the past are still with us and losses of the future have already occurred.

The mug, in other words, is already broken. And also, it will always be whole.

“You see this goblet?” asks Achaan Chaa, the Thai meditation master. “For me this glass is already broken. I enjoy it; I drink out of it. It holds my water admirably, sometimes even reflecting the sun in beautiful patterns. If I should tap it, it has a lovely ring to it. But when I put this glass on the shelf and the wind knocks it over or my elbow brushes it off the table and it falls to the ground and shatters, I say, ‘Of course.’ When I understand that the glass is already broken, every moment with it is precious.”

I’m trying carry this philosophy with me as I begin to turn my thoughts toward home. The whales are still in the desert; the mug is already broken; I am still in Minneapolis, and I will also, forever, be here.

Yours—L.