lebanese dispatch: castles by the sea

A thirteenth-century castle in Sidon, originally built as a Crusader fortress.

My dear friend,

I’ve written to you, I think, about driving in Egypt. It’s noisy and wild: there are no rules except for the basic principle of physics that no two objects can occupy the same space at the same time. There are few stop lights, few seat belts. Pedestrians walk into the road without warning or reason. Last week, when C. was on the bus home from campus, the driver missed his exit and then proceeded to reverse a half mile down the freeway in order to rectify his error. Did I mention that it was rush hour?

We’ve never driven a car in Egypt. Last spring, we rented one in Jordan; and last week, we rented one in Lebanon. Driving in Lebanon is not quite as wild as driving in Egypt would be; but if there are a few more rules of the road, there are also other challenges. For instance, because the government cannot afford to pay for electricity, ninety-nine percent of the stoplights in Beirut are not functioning.

Midwestern drivers are so famously passive that when we reach a non-working stoplight, which we are told to treat as a four-way stop, we spend most of our time at the intersection waving other drivers to go on ahead of us. (It’s just good manners, no?) This was not the case in Beirut, where every intersection was a chaotic heap of cars, horns, and pedestrians. We learned quickly that if we waited for our turn, we’d be waiting forever.

View from the ramparts of the Sidon Castle.

So, we took a couple deep breaths and steered straight into the madness. What choice did we have? We needed to get out of Beirut in order to see Sidon (Saida), a coastal town founded around five thousand years ago. Originally Phoenician, the town passed through the hands of the Persians, the Greeks, the Romans, the Crusaders, the Mamelukes, and the French before taking up its mantle as third-largest city in independent Lebanon. When we walked the grounds of the 13th-century Crusader castle, the space felt so empty and the sea so peaceful that it was hard to imagine the violence that rocked its shores over the centuries—most recently during the Lebanese Civil War.

One of the highlights of Sidon is wandering through the ancient stone tunnels and archways of the old souk. You can find shiny bags of chips alongside giant sacks of spices, falafel next to lingerie, tea sets nestled beside electronics. In its earliest history, Sidon was famous for the production of glass and of a purple dye drawn from murex shells. The color was so rare, so expensive, that it became the mark of royalty for centuries after. Much later, residents began manufacturing soap. These days, a 17-century soap factory has been repurposed as as a museum.

We paid an entry fee of about fifty cents and were shown around by an English-speaking guide. I don’t remember much of what she told us—I was too distracted by the walls of soap and the cloudy scents of lavender and rose.

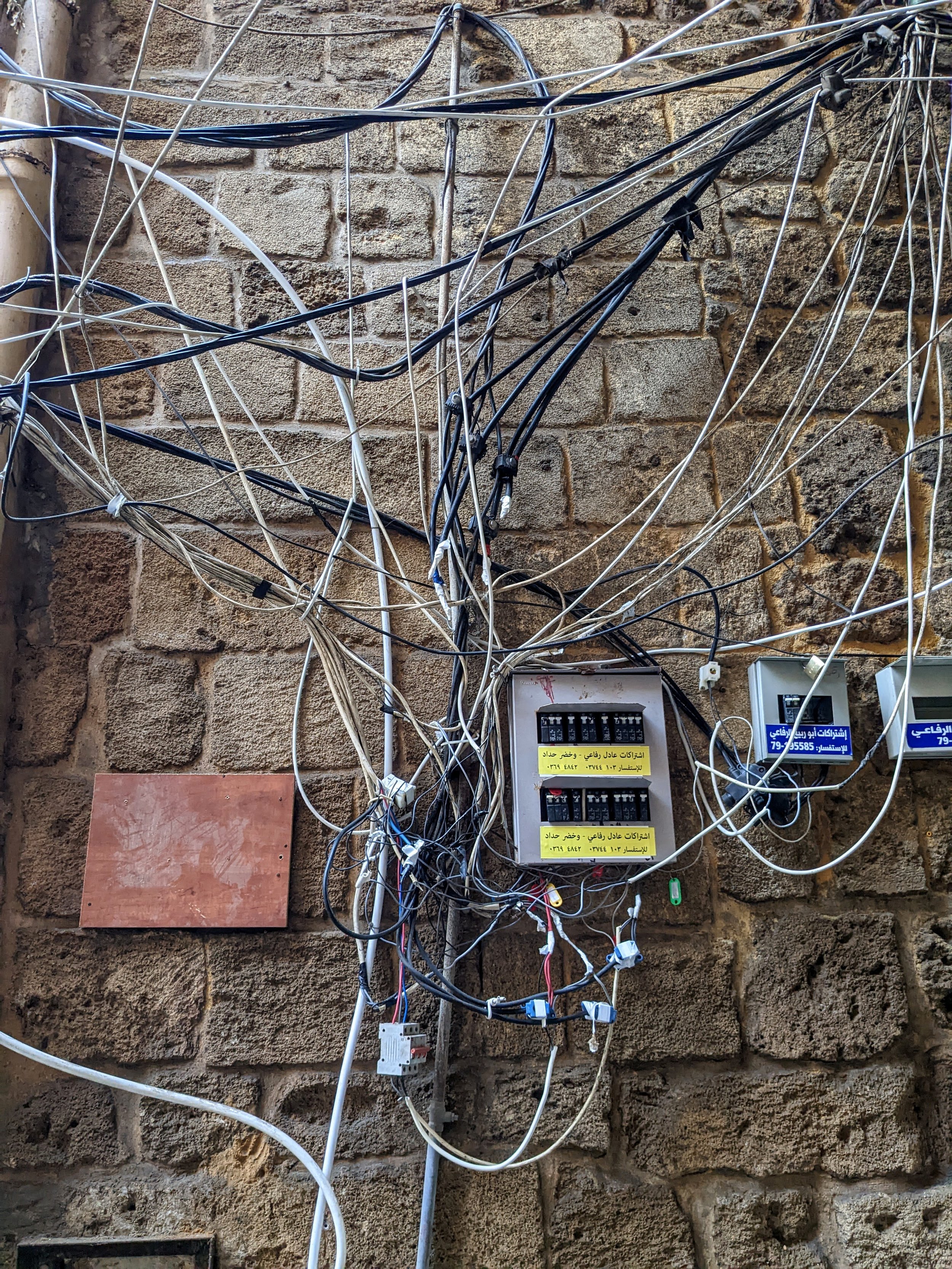

The soaps were nice, but I found myself most intrigued by something else I’d noticed as we ambled through the old town: the electric wires looping over each other, criss-crossing the sky, in bundled, tangled knots like—well, like cars at a Beirut intersection.

It didn’t seem like the safest electrical situation. But then, I was afraid of plugging lamps into outlets until I was in middle school, so perhaps I’m not the best person to judge. C. is still sometimes surprised to find, after we return home from a few days away, that I’ve unplugged all of our kitchen appliances and bedside lamps to reduce the risk of fire while we were gone. Usually he doesn’t mind, but when he wanted to take a shower after a night in the desert and learned that I’d unplugged the water heater, he wasn’t super pleased with me.

The energy situation in Lebanon is, as I mentioned, complicated and fraught. In each hotel we stayed, no matter the city, the power went off between about 3 and 6 in the morning and 3 and 6 in the afternoon.

We were warned of this ahead of time, as the rationing of power has become a part of daily life.

I found Sidon intriguing for its ancient history, its many layers; for the tranquility of the sea juxtaposed with the frenzied hustle of the city.

Yet it did not strike me as a particularly restful place. So I was glad when we returned to the car and hit the road again, sliding a little further south down the coast toward Tyre.

Our route from Beirut in the morning to Sidon (Saida) in the afternoon to Tyre in the evening.

Within a few minutes, we were out of the traffic and into the banana fields.

We passed a few unattended checkpoints, and a few checkpoints with men in military gear who glanced lazily into the car and waved us through.

Tyre, when we arrived, was lovely. The light turned white stones rose-gold; plants dripped from balconies. The sound of birds winging through a giant tree outside our hotel room window was absolutely deafening.

We walked through winding, cobblestone-streets that reminded me of small Italian villages, greeting stray cats and pausing to admire the many shrines. It was good to be out of the car.

Eventually we emerged at the harbor and settled into a little restaurant that served us fresh fish, salad, hummus, and fries. I pulled out our travel backgammon set, hoping the proprietor would be impressed by our familiarity with this popular local game, but instead he just shook his head. “We have many bigger boards inside,” he said. “You didn’t need to bring your own.”

Tyre was first established as a colony of Sidon, and one that was most likely controlled for a time by Egypt. Centuries later, colonists from Tyre, in turn, founded Carthage in North Africa: the city in which Dido waylaid Aeneas. Like every site in Lebanon, Tyre moved through many empires: it was Phoenician, then Assyrian, then Persian. It famously withstood an attack from Alexander the Great for seven months, though he wasn’t happy when he finally won: he killed 10,000 inhabitants and sold 30,000 into slavery. Before Alexander, the town had existed partly on the mainland and partly on an island. But after conquering the mainland, he used the ruins to build a causeway. The island became a peninsula, and the causeway was never removed.

Its seaside location was both a blessing and a curse: it easily became a maritime hub, outperforming even Sidon for its bustling commercial trade; but it was also too appealing for emperors and invaders to resist.

For me, the most enthralling part of the city were the Roman-Byzantine ruins that have recently been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site—in part to protect them from pollution and looting. The ruins were damaged during Israeli bombardments of South Lebanon in 1982 and 1996.

It’s pretty amazing to round a corner and see the ruins just—there, fenced off as if this is just another parking lot.

We strolled between columns, admired mosaics, paused beside bathhouses, and rested for a while in the shade of a stadium.

I had read that there are other ruins just off shore, beneath the water.

But though I searched the waves as best as I could, I saw only a person fishing.

We’d had a lovely breakfast in the hotel garden, so after we had our daily fill of ruins, we continued on our way.

We drove past breathtaking mountain vistas and homes perched on hillsides. Most of the buildings we saw looked uninhabited, and the roads were often empty but for us.

Near the end of our journey, we found ourselves at one last seaside fortress: Byblos.

If you’re thinking that “Byblos” sounds an awful lot like the root of a word such as “bibliography” or “bibliophile” or even “Bible,” you’re not wrong. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, “The name Byblos is Greek: papyrus received its early Greek name (byblos, byblinos) from its being exported to the Aegean through Byblos. Hence the English word Bible is derived from byblos as ‘the (papyrus) book.’” It’s interesting to think that the word for “book” was originally used not to describe the object itself, but the place through which the object traveled. As I walked among the ruins, I found myself thinking about how I, too, have been shaped—if not named—by the places through which I’ve traveled.

The ancient city’s literary importance doesn’t end there. This is also the place that witnessed the emergence of the Phoenician alphabet, which—if scholars are correct in identifying it as a predecessor to the Greek alphabet—eventually became our alphabet.

Like Sidon and Tyre, Byblos is often called “one of the oldest continually-inhabited towns in the world.” Once more, I found myself walking upon layers and layers of history: houses from the Neolithic Period (8000-4000 BC), Phoenician ramparts and cemeteries (1200 BC - 600 BC), a Roman ampitheater (65 BC-400 AD), a Crusader fort (1100 AD). There are temples, tombs, wells, columns, ramparts, baths, homes.

It’s a lot to take in.

But as I said to C. during our explorations, I think I may actually prefer Byblos to Baalbek. Byblos is even more complicated, more layered—and also, it feels more representative of daily life. Baalbek is comprised of temples and altars. Byblos contains houses from the New Stone Age that were constructed with actual stone floors. One can imagine people living here, working and walking and playing here.

The strong link between Byblos and ancient Egypt was on my mind as we wrapped up our journey and prepared to return to Cairo. Evidently there are mentions of Byblos in Egyptian records all the way back to the Old Kingdom, since it was from Byblos that the Egyptians acquired the cedar wood they used to build sarcophagi and the royal boats they buried with the pharaohs in their tombs.

We crossed through the market stalls, bought a fresh fruit juice for the road, started driving back to Beirut, and were rear-ended in traffic right outside the city. We were fine; the driver behind us was fine. We learned later, after his passenger stalked out of his car and stormed down the highway without a word to any of us, that he’d just broken up with her.

“I told her I never wanted to see her again,” the young man declared. “I told her I was going to block her. That’s when I hit you.”

Wanting to offer sympathy but uncertain how, I held out an apple we’d brought back with us from the mountains. (He didn’t take it.)

Back in Beirut.

I’d been so preoccupied with my musings over the thousands of years of history we’d spent the week walking across that it was startling and disorienting to remember that sometimes it only takes a fraction of a second for everything to change.

As we finally made it back to Beirut and rolled past buildings pockmarked with bullet holes from the civil war and mounds of broken glass from the port explosion, it was hard not to see history as exactly this: an accumulation of those partial seconds when something ended or started, shifted or shattered, irrevocably changed.

Yours—L.