lake nasser

My dear friend,

Throughout our travels, we’ve spent time with many tour guides. There was the middle-aged Cairene who cruised down the Nile with a cowboy hat and walking stick and who told us that he’s not in a hurry to get married because his mother and sisters still do his laundry for him. There was the young woman in Beirut who sat us down above an old Roman bathhouse and told us not to worry about saving anything for the future because the future is uncertain and the government will probably steal everything you’ve saved, anyway. There was the Bedouin Jeep-driver in the western desert who lied to the police in order to sneak us into a set of forbidden tombs. As we scrambled over dunes littered with sun-bleached bones, he picked up a jawbone studded with teeth and announced: “This is people.”

And a few weeks ago, on Lake Nasser, there was Ahmed: a passionate and well-read Egyptologist who wrote an entire book about why ancient Egypt declined and how modern-day Egypt could restore its former glory. Ahmed, without a doubt, was the most knowledgable guide we’ve met so far. The number of names and dates and details that spun from his tongue were astounding. The one thing that he didn’t know—which surprised us, since he’s a guide who spends a great deal of time on Egyptian cruise boats—was how to swim.

We learned this when we came across a half-sunken abandoned ship on our first night on Lake Nasser. From a distance, the Imhotep (named after the famous Egyptian architect responsible for Djoser’s step pyramid) looked bewitchingly eerie; when we drew closer and gazed across the rickety planks that led from the shore to its deck, it seemed eerier still. One of the only facts I knew about Lake Nasser before our visit was that nearly all the remaining crocodiles of the Lower Nile were now gathered in these waters.

At first, Ahmed declared that we would not be walking out to the ship. But then he saw that the other guide on our boat, a French speaker who was accompanying the other two passengers, was already halfway across the planks. Not wanting to lose face, Ahmed took a huge breath and led us out across the water.

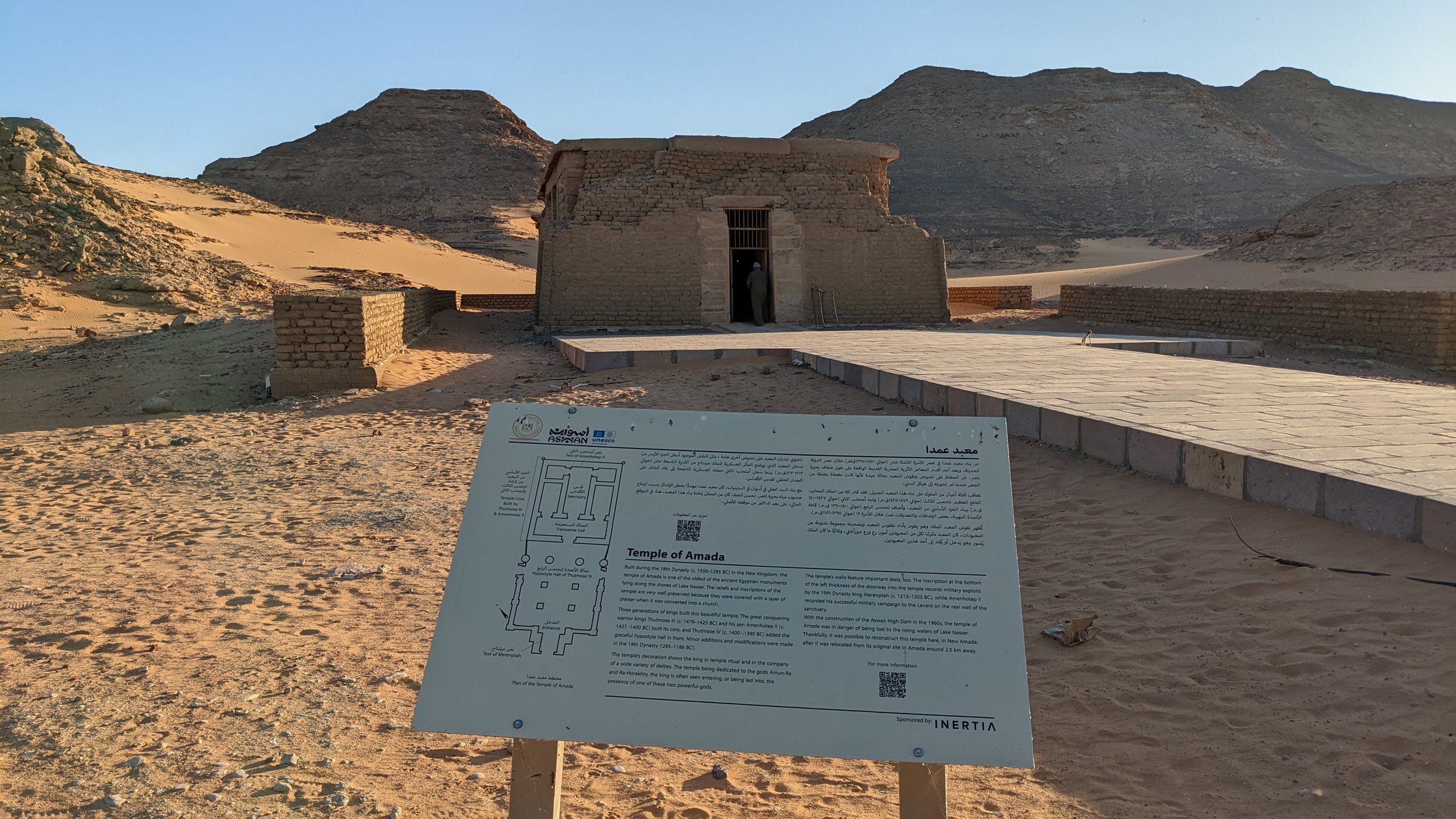

The ship, he explained upon our safe return, had been used in the 1960s to help dismantle and rebuild the nearby temples of Amada and Derr right before the inauguration of the Aswan High Dam created Lake Nasser. If the temples had not been moved out of the water’s way, they would have been submerged. Thanks to an international rescue effort led by UNESCO, the majority of the ancient sites that would have ended up beneath Lake Nasser were salvaged and preserved before the waters rose in 1970.

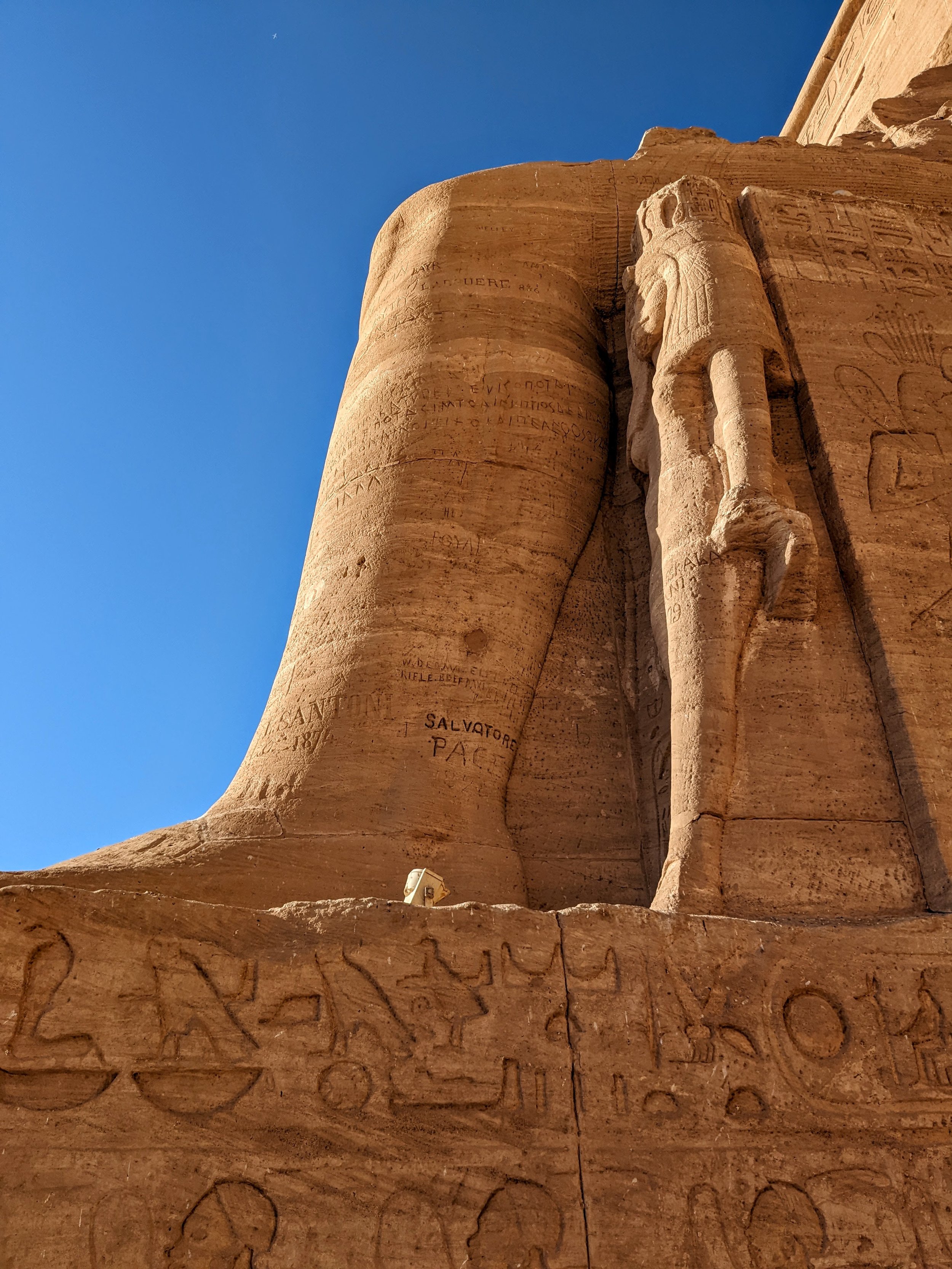

The most famous operation, by far, was the rescue of Abu Simbel: a two-temple complex designed and carved out of a sandstone cliff during the reign of Ramses II (1279-1213 B.C.), a pharaoh of the New Kingdom who filled Egypt with statues of himself. The massive likenesses that flank the main entrance to Abu Simbel are marvelous and intimidating. One of his wives (he had over 200) and a few of his children (he had 96 sons and 60 daughters) earned tiny statues beside his impressive calves or between his humungous feet.

Later, Ahmed told us that it is essential for modern Egyptian leaders to model themselves after pharaohs like Ramses II. Examples of good leaders, he said, were former president Gamal Abdel Nasser (who nationalized the Suez Canal, pushed for modernization, and promoted pan-Arabism), current president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi (whose “Make Egypt Great Again” approach includes iron-fisted rule, horrific prisons, and general human rights violations), and soccer star Mo Salah (the most famous Egyptian in the world, who plays for Premier League club Liverpool).

Like many sites along the Nile, the towering Ramses statues were buried under sand for centuries. Once archaeologists uncovered the temple in the 1800s, they found three progressively smaller halls, most of which were decorated with scenes of the pharaoh’s military victories. (The first peace treaty in history, commemorated in stone at Abu Simbel, was contracted between Ramses II and his enemies, the Hittites.) On two days of the year (around February 22 and October 22), the sunlight aligns with the temple opening and illuminates the statues of the gods in the innermost sanctuary. The only place the sun never reaches is the face of the god Ptah, who is associated with the underworld and therefore always remains shrouded in darkness.

Beside the main temple is a smaller structure decided to the pharaoh’s favorite queen, Nefertari. Archaeologists say that Nefertari was well-loved because the statues of her in front of this temple are the same size as those of Ramses II—even though there are two of her and four of him. She’s also only the second queen in the history of ancient Egypt to have a whole temple to herself!

On the boat that evening, Ahmed showed us some grainy video footage of the rescue of Abu Simbel and several of the other temples along the shores of Lake Nasser. (This isn’t the exact video we watched, but it conveys the general idea.) It was nice to have that context when we visited the temple of Amada the following morning. Built by Thutmose III and considered the oldest Egyptian temple in Nubia, Amada was lifted onto railroad tracks and shifted very slowly to higher ground because engineers feared that cutting it into blocks (as Abu Simbel was) would damage the artwork inside. In the video we watched, workmen deconstructed the tracks behind the temple in order to reconstruct them ahead of it. The process was painstaking, laborious, and difficult—but the art was preserved.

Our boat was the only one docked at this site, and so we ambled from the Temple of Amada to the Temple of Derr without encountering any other visitors. The path was sandy and golden, and the lake was serene.

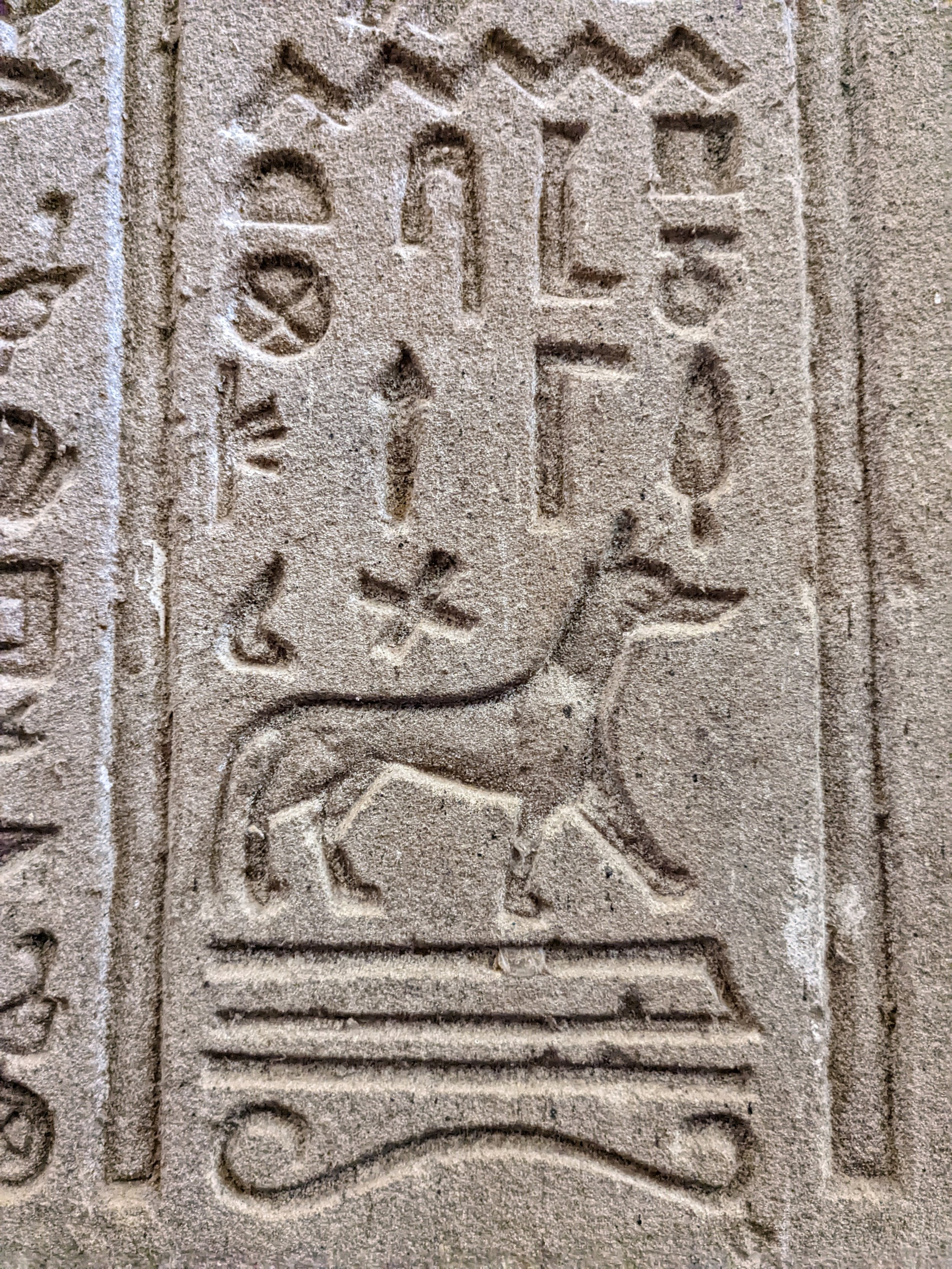

The rock-cut Temple of Derr, another of Ramses II’s productions, features two great columns and multiple reliefs of the pharaoh engaged in battles or purification rituals or offerings to the gods. The original colors remain vivid, and I stood for a several minutes admiring the pale blue sky behind the green leaves of a tree that haloed the pharaoh.

Back on the boat, we breakfasted on the Egyptian staples: eggs and falafel and ful (mashed fava beans) and yogurt and fruit. We made a little conversation with the French tourists and their guide. Ahmed grabbed a piece of bread and vanished below deck.

We cruised for a few hours until we reached Wadi es-Sebua, or “Valley of the Lions”: so-named for the sphinxes that fill the court leading up into yet another temple built by Ramses II. His statues here are smaller in size, and often missing the heads that were stolen by thieves. Like many temples in the area, this one was converted into a church by early Christians around the 5th century A.D. Sometimes they chiseled away the original carvings, but sometimes they merely plastered over them and painted the plaster with their own images. In doing so, they actually helped preserve the originals underneath.

On the walk from Wadi es-Sebua up to the Temple of Dakka (originally dedicated to Thoth, the ancient Egyptian god of wisdom, and later converted into a church and Roman fortress), Ahmed told us all the reasons why Ramses II was definitely not the pharaoh who enslaved the Israelites and suffered the plagues. Since it seems that scholars are still debating this question, we found Ahmed’s absolute certainty intriguing. Was it because he didn’t want one of the greatest kings of Egyptian history to be associated with with the cruelty and despotism of the ruler in that ancient story? If so, how does Ahmed reconcile his admiration of President el-Sisi with the country’s ongoing human rights violations?

(El-Sisi was under particular scrutiny around the time of our boat trip because Egypt was hosting the climate conference in the seaside town of Sharm el-Sheikh and protestors were trying to shed light on the treatment of Egyptian political prisoners such as Alaa Abd el Fattah.)

Although el-Sisi has not filled Egypt with statues of himself, he has filled it with billboards of himself. It’s difficult to travel any significant distance by car without seeing one, or several. The president’s distant, half-smiling gaze bears a definite resemblance to the expression of Ramses II. “As long as I’m here, I might as well lead you,” the faces seem to say. “I mean, since that’s clearly what you want.”

The president’s insistence on building a new capital in the desert has been called a “neo-pharaonic campaign” that has destroyed and uprooted neighborhoods of both the living and the dead. Such “megaprojects,” according to the New York Times, “mostly constructed by the country’s powerful military, make Mr. el-Sisi the latest in a long line of Egyptian leaders, stretching back centuries, who have sought to mirror their authority in imposing structures that rise from the desert.”

“So what if I have palaces?” the president is reported to have said in response to criticism. “They are for all Egyptians.”

The vast majority of Egyptians, of course, cannot afford the new housing or access the new buildings, just as the majority of ancient Egyptians were not allowed to enter the temples or tombs we buy five-dollar tickets for now. C. recently finished reading Toby Wilkinson’s The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt, a book which argues that the architectural and artistic glories of Egypt, which so enrapture us today, were made possible by a dictatorial, authoritarian regime that made the lives of common people short and hard.

Despite all of the conversations we had with him on and off the boat, Ahmed never alluded to such critiques in his praise for past and present kings.

He did, of course, have plenty to say about the American government. He described in detail his theory that America was responsible for the 9/11 attacks and that the U.S. has been funding ISIS for years. Remarks such as these complicated our relationship with Ahmed: we trusted his extensive, impressive expertise in his field, but we grew wary whenever he shifted to the realm of modern politics. We knew that on this latter topic, we were bound to disagree.

The boat doesn’t sail after dark, and so we always docked by sunset. We read, or played dominoes with the French tourists, or taught them how to play backgammon. We drank teas and fruit juices in between meals of stews and meats and potatoes and fish that the crew pulled out of the lake and fried up right on the shore. While they fished, I wandered around collecting volcanic rocks that C. said I couldn’t bring home. (I had collected a few too many rocks already.)

When I asked a friend of mine who cruised the Nile with us last year what she thought about the experience, the first element she reflected on was our relationship with our guide. “It’s weird that for a handful of days, your life becomes so intertwined with this stranger’s life,” she said. “All the meals together, all the conversations—it’s unexpectedly intimate.”

Boats on the Nile in Aswan.

Her remark got me thinking about our relationship with our first Arabic tutor, an Egyptian woman we’d met through the online language app Italki. We studied with her for about six months, until she told us that she wouldn’t be able to teach us anymore because she was moving away and starting a grad program. The grief I felt at this news was acute. I see now that our relationship with this tutor was more intimate than I’d realized at the time: we went into every language lesson sounding childish and stupid, but she never once laughed at us. We were powerless, and vulnerable, and ignorant, and the only way for us to learn anything was to trust her completely.

Despite our political differences, we were required to put a similar kind of faith in all of our guides. Our lives were, quite literally, in their hands.

If they had chosen to abandon us in the desert or on an island, we would not have been able to find our way back. Usually, our phones were without service.

But neither Ahmed nor the others ever abandoned us. They always shuttled us safely from ruin to ruin, shore to shore, with patience and expertise.

On our last evening on the lake, right before sunset, we visited Kalabsha, a Roman temple (30 B.C.) originally dedicated to the Nubian sun god and later repurposed as a Christian church. A friendly dog greeted us at the dock and, as we were the only visitors, followed us as we walked between the columns and admired carvings of the falcon-headed Horus and images of pharaohs bearing loaded plates of offerings for the gods.

A short walk from Kalabsha…

… was Beit el Wali, a fitting place to end the tour because it, too, was built by Ramses II. By now we were familiar with scenes of his military victories and the way he positioned himself among the gods.

Our stroll back to the boat—Ahmed hurried us along, because the sun had definitely set by then—took us past the Roman kiosk of Qertassi, with its six sandstone pillars glowing in the last bit of light.

Sometimes, when I try to make sense of everything our guides have told me about ancient Egyptian history, I find myself frustrated by my inability to keep it all straight. I am so overwhelmed by the number of centuries and dynasties, by the names of gods and pharaohs, by the ruins built on top of other ruins, that all I have room to carry with me are impressions: the sun setting behind the kiosk, the statues looming over the temple, the colors of ancient stone leaves. If Ahmed had given me a final exam on our last night aboard, I certainly would have failed.

But he didn’t give us an exam. Instead, right before he left us, he requested a copy of the photo I’d taken of him on the rickety planks right before he returned safely from the sunken ship to shore. “Now, this!” he exclaimed, with no trace of irony. “This will go down in history!”

In the end, what was most marvelous about the tour of Lake Nasser was not the temples themselves (although of course they were stunning), but rather the fact that they had been built not once but twice. For an international effort to move so quickly, with so much cooperation, with so much success, says something, I think, about how individuals around the world remain astonished by and invested in Egyptian history. Even if we live thousands of miles away from ancient Egyptian art and architecture, we believe in their value and we know that they’re worth saving.

I completely understand Ahmed’s passion for the glories of the pharaohs, the temples, because I, too, felt a similar awe and wonder when I first learned of this history in the fifth grade and I feel it still, even more so, with every cartouche I encounter. You might think it would grow old—Ramses statue after Ramses statue, falcon-god after falcon-god. But, amazingly, it doesn’t.

Yours—L.