alexandria the great

My dear friend,

One of the books I brought to Egypt is a hefty hardback called 100 Poems to Break Your Heart. When I discovered the volume at a bookstore in Raleigh two weeks before our departure, I envisioned myself lounging on our Egyptian balcony, reading a few poems first thing in the morning as I sipped a honey latte. I was certain that my Egyptian self would be able to create the space for poetry and reflection that my American self could not.

But we’ve been in Egypt for nearly three months now, and I’ve read about ten poems. Fortunately, one of those poems was C.P. Cavafy’s “The God Abandons Antony,” in which the Greek poet imagines Mark Antony’s final night in the Egyptian city of Alexandria in 30 B.C. (I’ve enclosed the poem with this letter.) As Edward Hirsch, the editor of this volume, explains: “Mark Antony loved Alexandria, the Greek-speaking metropolis of the Roman east. Before his rival, Octavian, marched into Alexandria to take the city, Antony stabbed himself and died in Cleopatra’s arms.”

Cavafy’s poem, whose lines inspired Leonard Cohen’s haunting song “Alexandra Leaving,” places Antony “at the window,” listening to the “exquisite music” of a “strange procession.” The speaker instructs the doomed Antony to be brave, to be gracious, to be grateful, even, as he bids farewell “to the Alexandria” he is “losing.”

When I first stood at the window at our hotel (the faded, beautiful Cecil) in Alexandria, I was greeting the city—not bidding it farewell. Yet as I gazed over the arc of the corniche and listened to the waves lapping beneath the noise of the traffic, I, too, felt an unexpected affection for this unfamiliar place. And I, too, already sensed that after I returned to Cairo, I would miss it.

It was Alexander the Great who chose this harbor as his capital once he gained control of Egypt in 332 B.C.—but he died overseas and never saw the city completed. The Ptolemies, who followed him, transformed Alexandria into the intellectual and cultural lodestar of the ancient world, with the famous library and marvelous lighthouse that continue to draw visitors here even though both structures have long since vanished from its shores.

Cleopatra, the last of the Ptolemies, the final Egyptian pharaoh, and the lover of Mark Antony, lost Alexandria to the Romans in 30 B.C. The city maintained its status as the Egyptian capital of the Roman and Byzantine empires, but when the Muslim army conquered Egypt in 641 A.D., Alexandria was passed over in favor of a new capital at Fustat (now part of Cairo).

The city languished out of the spotlight for over a thousand years. Then, under Mohammad Ali’s leadership in the nineteenth century, the city experienced a cultural and economic revival thanks to a reconstructed harbor, a new arsenal, and a fresh canal that reestablished a silted-over connection between the Mediterranean and the Nile. European merchants flocked to the city in droves. In 1956, after Israel, the U.K., and France invaded Egypt in an attempt to regain control of the Suez Canal, President Gamal Abdel Nasser retaliated by ousting French and British citizens and nationalizing foreign businesses. Although most Europeans departed, their presence lingers in the city’s antique hotels and gleaming patisseries.

Divers can still see the ruins of the lighthouse and of Cleopatra’s palace beneath the sea. In 2015, the Supreme Council of Antiquities announced plans for an underwater museum in Alexandria that would allow visitors to view the wreckage of the city’s history through a network of fiberglass tunnels. According to one guidebook, the developers have been stalled by their inability to keep algae from growing on the tunnels and blocking the view. (An underwater museum would also require government officials to confront the massive plastic pollution problem in the Mediterranean, as well as the influx of sewage and chemical waste flowing in from the Nile.)

We admired the sea from afar and keep our explorations on land. (C. has a fear of large underwater objects, so lighthouse-diving was not for us.) After snagging a cream-filled doughnut from the established patisserie Délices (definitely worth the cost of the train ticket), we strolled through the ruins of Kom el-Dikka, an ancient Roman complex that included an amphitheater, a series of bathhouses, residencies with elaborately tiled floors, and a long row of university classrooms. C. peered into one of them and asked (rather mournfully): “Do you think that their students did the reading?”

Kom el-Dikka, which means “mound of rubble,” is not to be confused with the Catacombs of Kom es-Shoqafa, or “mound of shards.” In a country as rich with archeological treasures as this one, perhaps people grew tired of coming up with fancy names for buried ruins.

Kom es-Shoqafa is the largest known Roman burial site in Egypt, and was famously discovered when a donkey suddenly dropped through an unseen hole in the ground. Perhaps I shouldn’t be surprised by how many ancient treasures have been found by happenstance, but I still have trouble wrapping my mind around just how ancient something must be in order for it to have been built, forgotten for a thousand years or more, and then rediscovered.

Here’s one of my favorite facts about Egypt: when Cleopatra and Julius Caesar (her boyfriend before Mark Antony) sailed down the Nile, they did not see the sphinx because it had already been buried in sand for a thousand years. Also: we are closer in time to Cleopatra than she was to the pharaohs who built the Great Pyramids. How incredible is that?

The catacombs, though not as splendid as pharaonic tombs in sites such as the Valley of the Kings, are the perfect blend of cool, gloomy, and kitschy. The network of tombs began as a small family burial crypt but was later expanded to make room for three hundred bodies. Corpses were lowered through a central shaft. Then family members descended to an underground dining area to eat and drink on long stone couches while raising their glasses to the dearly departed.

Above ground, in sunlit streets and narrow alleyways, C. and I stumbled upon our own unforeseen treasure: a street market with house pets! At first, it felt whimsical. Parakeets, chickens, parrots, goldfish—they all waited in boxes or crates on card tables. Then we rounded a corner and found the kittens. Another corner: the puppies in cages. The final street was packed full of people with packs of dogs on leashes: some golden retrievers, some muzzled German shepherds, some unidentified mixes straining at their chains. I was already feeling anxious about the dogs and the sellers’ keen gazes—and so when I realized that a kid’s hand was reaching into my bag and I was the only woman among the hundreds of men crowded into the street, I veered off the main road and pulled C. along with me.

In a side street, while leaning against a wall and catching my breath, I saw a car with an empty pigeon crate on the roof. Upon closer inspection, I found the pigeon in the passenger seat. Perhaps he, too, had been overwhelmed by the market and had retreated to a quiet place to think.

In this way, Alexandria is much like Cairo: full of whimsy and delight and unexpected beauty, if you’re willing to shake off some unwanted attention and work your way through a few heaps of trash.

When we traveled 45 minutes up the coast for a seaside lunch in Abu Qir, we found the beach beautiful but neglected. As C. and I stood on a boardwalk and gazed out over murky puddles rippling with plastic bags, I announced: “This isn’t what I expected.”

(Although it would have been easy to deplore the Egyptians’ treatment of their beaches, doing so would have been hypocritical. The only reason American plastics aren’t filling up our own beaches is because we’re exporting them to someone else’s. As the Guardian reported in 2019, “hundreds of thousands of tons of US plastic are being shipped every year to poorly regulated developing countries around the globe.” When 187 countries recently “signed a treaty giving nations the power to block the import of contaminated or hard-to-recycle plastic trash,” the United States refused to sign. Our plastics may not be in Egypt, but they’re certainly in “some of the world’s poorest countries, including Bangladesh, Laos, Ethiopia and Senegal.”)

As we waited for the chef to grill the fish we’d selected from a pile of ice in the front of the restaurant, we watched a group of kids playing soccer in the sand and saw a cat kill a bird in the tall grass. From the deck where we were sitting, we couldn’t see the trash as clearly—but of course this other “mound of rubble” remained even after the sun dropped down and the sea went dark.

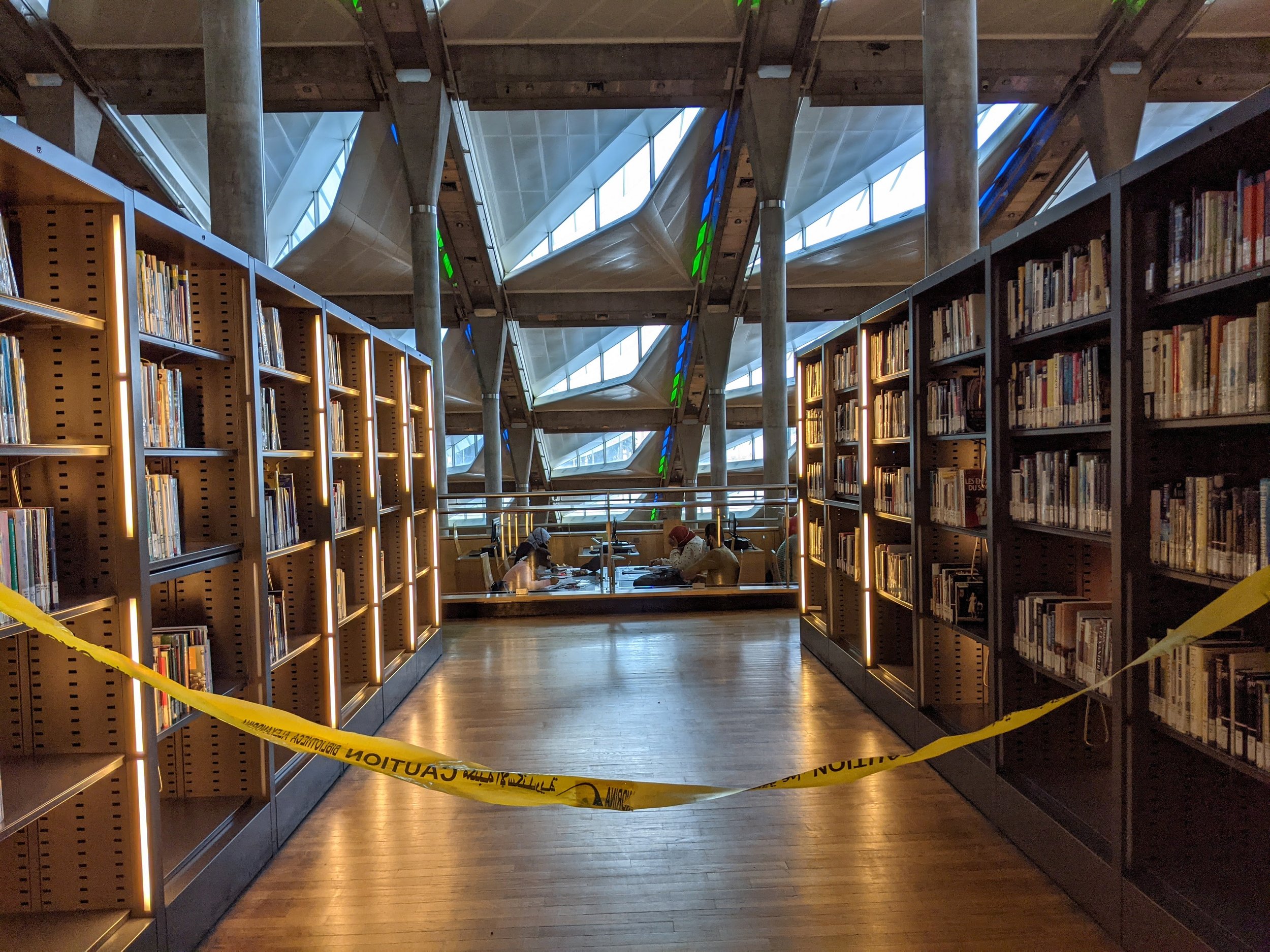

Although I bid an affectionate farewell to Alexandria the following morning—taking my cue from Cavafy’s poem, of course—it turned out that we were not separated for long. Two weeks later, we returned to the city with my parents in order to visit the new library (completed in 2002) that had been closed during our first visit. The building has been constructed to look like a sun rising out of the sea, with walls of Aswan granite that are carved with characters from 120 different languages.

Inside, we found ourselves in a massive, gleaming reading room. The architecture is breathtaking, but the contents are not as impressive. Although the library has shelf space for eight million books, the actual number is far, far fewer—mostly because so much money was spent on the construction that there were not enough funds left for books. Despite the symbolic links between this building and the ancient, lost library of Alexandria, I found myself thinking more about the differences between them. The ancient library was said to hold a copy of every text that existed in the world up to that time. In comparison, this library could only be a husk, a shell, a gleaming, empty imitation that offered great style with little substance.

Still, I chastised myself: it wasn’t right to feel disappointed when standing in such a beautiful place. What was I expecting, really? To be transported back in time?

One of the most intriguing elements of Cavafy’s poem is the way the speaker presents the relationship between Mark Antony and Alexandria. It is not Antony that is leaving Alexandria; rather, it is “Alexandria that is leaving.” The poem is called “The God Abandons Antony,” but it might also be called “Alexandria Abandons Antony”—because really, the image evoked is of a man standing at a window wishing for the city to remain what it always was for him. But cities are forever shifting, changing. We know that we can never exactly return to a place that we left—but if we stay where we are, even a place that we know and love can become unfamiliar to us. We cannot protect ourselves from change by standing still.

As Hirsch remarks: “The speaker can be read not only as a fictive contemporary speaking to Mark Antony about bidding farewell to Alexandria, but also as the poet talking to himself about leaving that beloved city at the end of his own life. At the same time the poem is advising the reader to face the music, as it were, to leave a treasured place with the serene bravery of a hero.”

Outside the poet Cavafy’s house in Alexandria.

As I prepared to leave the city for the second time, I found myself thinking about the distance between the Alexandria I imagined and the Alexandria I got. The imagined Alexandria was mythic, sparkling, clean—the real Alexandria was a little grimier, a little emptier, but somehow—because of this—more meaningful. The library may have disappointed, for example, but the tiny, overlooked Mahmoud Said Museum overflowed with astonishing paintings, evocative sculptures, and other treasures. We visited this space on our last morning in the city, which is maybe why I was so taken with it. I was learning to appreciate the city for what it was, rather than what I wanted it to be.

Outside the Mahmoud Said Museum.

When I returned to Cairo with my poetry book, having read exactly zero new poems on the journey, I decided that if I was willing to recalibrate my expectations for Alexandria, I ought to recalibrate my expectations for myself, as well. Egyptian Lindsay may not be reading as much as American Lindsay assumed she would be, but she’s doing other things: exploring, photographing, walking, teaching, talking—even, sometimes, writing.

Yours—L.

Enclosed: C.P. Cavafy’s “The God Abandons Antony”

When suddenly, at midnight, you hear

an invisible procession going by

with exquisite music, voices,

don’t mourn your luck that’s failing now,

work gone wrong, your plans

all proving deceptive—don’t mourn them uselessly.

As one long prepared, and graced with courage,

say goodbye to her, the Alexandria that is leaving.

Above all, don’t fool yourself, don’t say

it was a dream, your ears deceived you:

don’t degrade yourself with empty hopes like these.

As one long prepared, and graced with courage,

as is right for you who proved worthy of this kind of city,

go firmly to the window

and listen with deep emotion, but not

with the whining, the pleas of a coward;

listen—your final delectation—to the voices,

to the exquisite music of that strange procession,

and say goodbye to her, to the Alexandria you are losing.